Every autumn, I get emotional about grass. A whiff of earthy sod on a crisp fall morning means one thing to my mind: it’s cross country season. First as a spectator and then as a participant, I spent my September through November Saturday mornings from 1999 until 2011 running through the muddy grass of cross country courses. Sunday mornings were for church but also for scouring the sports section of The Sharon Herald to read results from that weekend’s invitationals. In the fall, life was cross country and cross country was life. And I loved it.

A few years back, running apparel company called Tracksmith launched a clothing collection celebrating the season of cross country. The landing page showed photos of athletes in the dewy fields of rural Vermont. Looking at them, I could nearly smell the grass. The headline reads, “The Great Equalizer,” followed by this paragraph:

Cross country is running at its best. Sure, we love to race the clock on fast courses tailor-made for personal bests. But do you know what’s even better? Slogging it out in the mud, just trying to beat the runner next to you up a hill and through the finish line. A solid time is gravy. Placement is everything. Cross country is all about team scoring, about doing your best whether you’re the first or seventh finisher for your squad. It’s about sprinting on grass across devilish courses in weather that might politely be called inclement. This combination of pure competition and natural challenges gives cross country races a vitality and unpredictability you can’t find on the track or roads. It’s the “great equalizer.”

Reading Tracksmith’s description of cross country got my heart racing. The thrill! The tenacity! The teamwork! Cross country really is running at its best. But as much as I love Tracksmith’s sentiments about cross country, the reality of the sport — including my own experience of it — is not all tales of glory. While cross country can be running at its best, it can also crush your dreams, wreck your body, and break your heart. There was a time in my life when it did just that. Then why do I still love cross country? I love it because of the impactful truth Tracksmith described: cross country is the great equalizer.

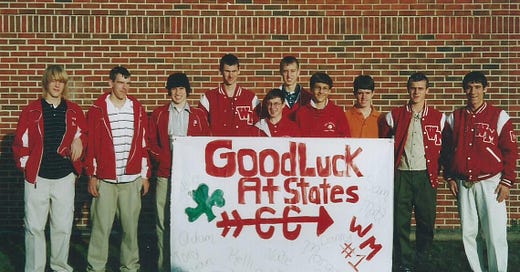

My past cross country teams were made up of teenagers coming from wildly different backgrounds and abilities. The team had a pair of siblings with jet-black hair who rode skateboards with hand-painted Anarchy symbols on them. There was a boy who could run fast (even in basketball shoes) and a girl wore fishnet fingerless gloves and a tutu to practice and almost always got last. And yet, our personalities, preferences, past performances, or parentage didn’t matter; we were a team. Some days, our team worked well together, encouraging each other through tough workouts and races. But other days, two teammates would decide to get high and accidentally run the other’s foot over with their car minutes before we were all set to race.

It was easy to grow angry with my team — to judge and resent them for messing up the plan, embarrassing me, or costing us the win. It was also easy to focus solely on my own performance, even if it meant throwing some elbows into the sides of my own teammates. Being on a cross country team could bring out my best, but it could also bring out my worst. Cross country is the great equalizer.

And yet when it was “my time” for running glory, I resented cross country’s great equalization. My junior year, we didn’t have enough girls to field a full team and consequently forfeited every dual meet. By the end of the season, I was burned out and bitter, resentful of being placed on a team of automatic losers. I could have accepted that just as hills and valleys are a natural and even good part of a cross country course, so were the ups and downs of being a part of a team of human beings. I could have seen that these challenges were ultimately strengthening me, helping me run with greater joy in both actual races and the race called life. But that’s not what I chose. It was not enough for me.

The following spring, I had a poor track season and then quit running altogether. Cross country had acted as the great equalizer; it had humbled me, and I hated it for that. In Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis writes, “For pride is spiritual cancer: it eats up the very possibility of love, or contentment, or even common sense.” For me, I nearly abandoned the sport I loved because I couldn’t overcome my pride: the cancer that prevented me from being content in the joy of running and of being and belonging on a team. I was running to be rewarded—to get my crown.

With my running but in many other places in my life, my pride, preferences, and ambitions have possessed me to reject God many times over. I have cursed the hills I must climb, heard the call to persevere and plugged my ears. I have resented the Bible for making it clear that I, along with everyone who has ever lived, am what one might politely call “sinful.” This is the great equalizer that has humbled me the most.

It does not feel good to be reminded of my depravity. In these moments, my pride jeers loudly from the sidelines, coaching me to abandon that theology and run my own race. But pride makes false promises. It hands out crowns that do not last. Pride is a thief that comes to steal and kill and destroy. So what is a prideful person like me to do? Is there no hope in this race called life? Am I permanently disqualified from the prize? Do I, as Tracksmith describes, slog it out in the mud, hoping that my best will be good enough to get me to the finish line?

Well, I suppose I could. But there is a better way. The better way is to remember that we are not running this race of life alone:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith. For the joy set before him he endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God. Consider him who endured such opposition from sinners, so that you will not grow weary and lose heart. (Heb 12: 1-3)

The best thing about this gift of grace is that it is offered to all of us: sinner or saints, winners or losers. Sin, though our great equalizer, does not permanently disqualify the skateboarding anarchist, the embittered team captain, or anyone else from turning to Christ, asking for forgiveness, and receiving it right then and there.

More than a year after my last cross country meet, I hobbled to the finish line of my first half marathon with a grimace on my face and tears in my eyes. I got 4,317th place, and I was overjoyed. I certainly did nothing to merit any of this reward; I didn’t suddenly become a better team player, and I can’t remember if I even repented. This is why, when I smell grass every fall, I become emotional. To me, the smell of grass is the smell of grace. The aroma reminds me of the things I learned running cross country, but also about the grace I was given to bodily, emotionally, and spiritually re-experience the joy of running. Though God might not have made me as fast as Eric Liddell, and yet “When I run, I feel His pleasure.”

A version of this post first appeared on Mockingbird, an organization devoted to “connecting the Christian faith with the realities of everyday life.” If you’ve got a hankerin’ you can read my Mockingbird archived essays here.